Copernical Team

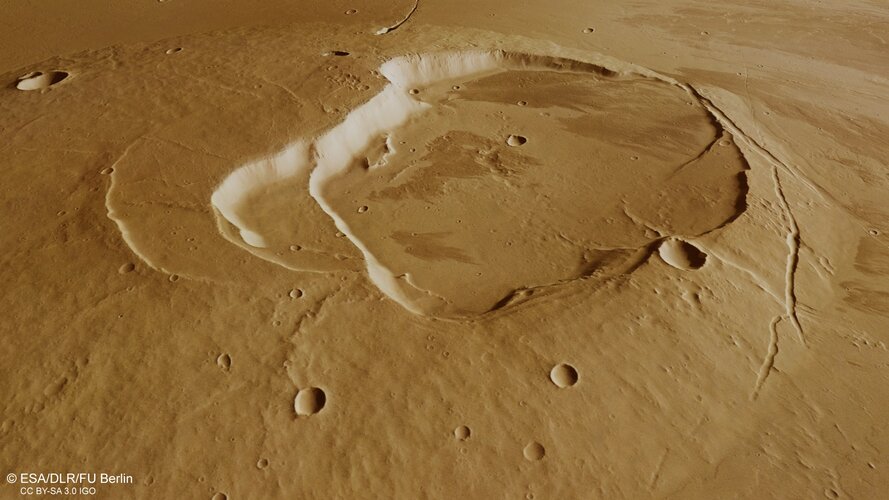

Making a splash in a lava sea

Volcanoes, impact craters, tectonic faults, river channels and a lava sea: a vast amount of information is captured in a relatively small area in this geologically rich new image from ESA’s Mars Express.

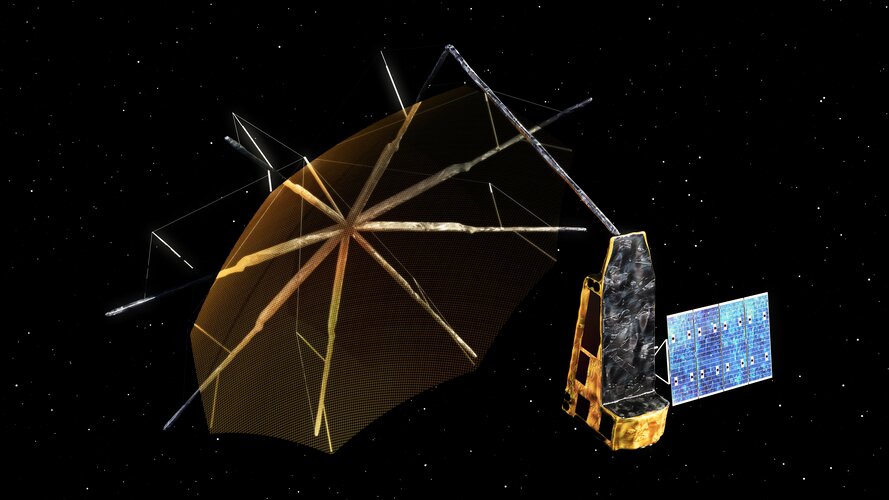

Forecasting performance of a space antenna – before it gets built

Antennas are among the most complex systems aboard a satellite – making them demanding to produce and often unpredictable to test. Tiny variables in their building, mounting or operation may impact their working performance in a big way. So ESA teamed up with Danish company TICRA to develop a method of forecasting such discrepancies well before an antenna construction even starts.

SpaceX delivers trio of Cape Town built satellites into orbit

SpaceX rocket launch Thursday carried three small South African-made satellites that will help with policing South African waters against illegal fishing operations.

Produced at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, the satellites could also be used to help other African countries to protect their coastal waters.

SpaceX's billionaire boss Elon Musk has given three nano satelli

SpaceX rocket launch Thursday carried three small South African-made satellites that will help with policing South African waters against illegal fishing operations.

Produced at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, the satellites could also be used to help other African countries to protect their coastal waters.

SpaceX's billionaire boss Elon Musk has given three nano satelli Dramatic Changes at Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai

When a volcano in the South Pacific Kingdom of Tonga began erupting in late-December 2021 and then violently exploded in mid-January 2022, NASA scientist Jim Garvin and colleagues were unusually well positioned to study the events. Ever since new land rose above the water surface in 2015 and joined two existing islands, Garvin and an international team of researchers have been monitoring changes

When a volcano in the South Pacific Kingdom of Tonga began erupting in late-December 2021 and then violently exploded in mid-January 2022, NASA scientist Jim Garvin and colleagues were unusually well positioned to study the events. Ever since new land rose above the water surface in 2015 and joined two existing islands, Garvin and an international team of researchers have been monitoring changes Providing GPS-quality timing accuracy without GPS

Synchronizing time in modern warfare - down to billionths and trillionths of a second - is critical for mission success. High-tech missiles, sensors, aircraft, ships, and artillery all rely on atomic clocks on GPS satellites for nanosecond timing accuracy. A timing error of just a few billionths of a second can translate to positioning being off by a meter or more. If GPS were jammed by an adver

Synchronizing time in modern warfare - down to billionths and trillionths of a second - is critical for mission success. High-tech missiles, sensors, aircraft, ships, and artillery all rely on atomic clocks on GPS satellites for nanosecond timing accuracy. A timing error of just a few billionths of a second can translate to positioning being off by a meter or more. If GPS were jammed by an adver Teaming up to deliver a new Airborne ISR SATCOM capability for MilGov Operators

Eclipse Global Connectivity, Smiths Interconnect and ST Engineering iDirect (iDirect) has announced their collaboration to deliver an integrated airborne Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (A-ISR) satellite communications (SATCOM) capability for military and government aircraft.

The solution, drawing on the extensive expertise of the three companies, will initially address the be

Eclipse Global Connectivity, Smiths Interconnect and ST Engineering iDirect (iDirect) has announced their collaboration to deliver an integrated airborne Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (A-ISR) satellite communications (SATCOM) capability for military and government aircraft.

The solution, drawing on the extensive expertise of the three companies, will initially address the be ULA launches two new Space Force tracking satellites into orbit

United Launch Alliance sent two space tracking satellites into orbit for the U.S. Space Force from Florida on Friday afternoon.

The Atlas V rocket lifted off as planned at 2 p.m. EST into a mostly cloudy sky from Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station near Kennedy Space Center. The single solid rocket booster strapped to the rocket also ignited, contributing to the rocket's fi

United Launch Alliance sent two space tracking satellites into orbit for the U.S. Space Force from Florida on Friday afternoon.

The Atlas V rocket lifted off as planned at 2 p.m. EST into a mostly cloudy sky from Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station near Kennedy Space Center. The single solid rocket booster strapped to the rocket also ignited, contributing to the rocket's fi Israel Knocks out simulated Iranian missile using Arrow-3 Interceptor

The Arrow-3 is one of several missile and drone defence systems in Israel's arsenal, and is meant to counter threats including long-range ballistic and cruise missiles. Unlike the Iron Dome air defence system - which has seen plenty of testing against simple Hamas rockets, the Arrow-3's capabilities have yet to be proven in a real-life conflict.

The Israeli military completed a test of the

The Arrow-3 is one of several missile and drone defence systems in Israel's arsenal, and is meant to counter threats including long-range ballistic and cruise missiles. Unlike the Iron Dome air defence system - which has seen plenty of testing against simple Hamas rockets, the Arrow-3's capabilities have yet to be proven in a real-life conflict.

The Israeli military completed a test of the How US Weaponises NATO to Maintain Its Own Space Dominance and Deter Russia and China

NATO released its "overarching" space policy on 17 January, stipulating that any space-based attack on an ally could trigger the alliance's collective defence policy under the bloc's Article 5. What's behind the renewed US focus on space and expansion of NATO activities there?

NATO's newly released space doctrine expands on the alliance's 2019 Space Policy - which recognised space as a new

NATO released its "overarching" space policy on 17 January, stipulating that any space-based attack on an ally could trigger the alliance's collective defence policy under the bloc's Article 5. What's behind the renewed US focus on space and expansion of NATO activities there?

NATO's newly released space doctrine expands on the alliance's 2019 Space Policy - which recognised space as a new China growing space capabilities represent 'Pacing Challenge' for US, Pentagon Says

China and Russia are both developing space capabilities but the difference is the speed with which China is progressing and it represents a "pacing challenge" for the United States, US Space Force Chief of Space Operations Gen. John Raymond said.

"I think they both are developing capabilities for their own use," Raymond said on Wednesday. "I think what's different is that China has gone ve

China and Russia are both developing space capabilities but the difference is the speed with which China is progressing and it represents a "pacing challenge" for the United States, US Space Force Chief of Space Operations Gen. John Raymond said.

"I think they both are developing capabilities for their own use," Raymond said on Wednesday. "I think what's different is that China has gone ve