Copernical Team

Hubble captures minor asteroid crossing image of background galaxies

A host of astronomical objects throng this image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. Background galaxies ranging from stately spirals to fuzzy ellipticals are strewn across the image, and bright foreground stars much closer to home are also present, surrounded by diffraction spikes. In the center of the image, the vague shape of the small galaxy UGC 7983 appears as a hazy cloud of light. UGC 7983 is around 30 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Virgo, and is a dwarf irregular galaxy—a type thought to be similar to the very earliest galaxies in the universe.

This image also conceals an astronomical interloper. A minor asteroid, only a handful of kilometers across, can be seen streaking across the upper left-hand side of this image. The trail of the asteroid is visible as four streaks of light separated by small gaps. These streaks of light represent the four separate exposures that were combined to create this image, the small gaps between each observation being necessary to change the filters inside Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys.

First Native American woman in space steps out on spacewalk

The first Native American woman in space ventured out on a spacewalk Friday to prep the International Space Station for more solar panels.

NASA astronaut Nicole Mann emerged alongside Japan's Koichi Wakata, lugging an equipment bag. Their job was to install support struts and brackets for new solar panels launching this summer, part of a continuing effort by NASA to expand the space station's power grid.

Mann, a Marine colonel and test pilot, rocketed into orbit last fall with SpaceX, becoming the first Native American woman in space. She is a member of the Wailacki of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in Northern California.

Wakata, Japan's spaceflight leader with five missions, also flew up on SpaceX. He helped build the station during the shuttle era.

Friday was the first spacewalk for both.

The pair will depart the space station in another month or so.

© 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

Astronaut Tim Peake assumes ESA ambassadorial role

Britain's Tim Peake steps down from ESA astronaut corps

Britain's Tim Peake has hung up his spacesuit, stepping down from Europe's astronaut corps to become an ambassador for space activities, the European Space Agency said on Friday.

Peake, who became the first British astronaut to visit the International Space Station in 2015, said it had been an "incredibly exciting and rewarding" 13 years.

"Being an ESA astronaut has been the most extraordinary experience," Peake, 50, said in a statement.

"By assuming the role of an ambassador for human spaceflight, I shall continue to support ESA and the UK Space Agency, with a focus on educational outreach, and I look forward to the many exciting opportunities ahead."

The ESA said that Peake had been on an unpaid leave of absence since October 2019, and had retired from active astronaut duties from the start of this year.

Galileo tribute unveiled as Juice says ‘Farewell, Europe’

A commemorative plaque celebrating Galileo’s discovery of Jupiter’s moons has been unveiled on ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, Juice. The spacecraft has just completed its final tests before departing Toulouse, France, for Europe’s Spaceport to count down to an April launch.

Falcon 9 launches sixth GPS 3 satellite

The sixth Global Positioning System III (GPS III) satellite designed and built by Lockheed Martin (NYSE: LMT) has been launched and is propelling to its operational orbit approximately 12,550 miles above Earth, where it will contribute to the ongoing modernization of the U.S. Space Force's GPS constellation.

GPS III Space Vehicle 06 (GPS III SV06) launched from Cape Canaveral Space Force S

The sixth Global Positioning System III (GPS III) satellite designed and built by Lockheed Martin (NYSE: LMT) has been launched and is propelling to its operational orbit approximately 12,550 miles above Earth, where it will contribute to the ongoing modernization of the U.S. Space Force's GPS constellation.

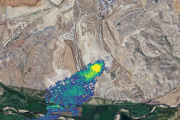

GPS III Space Vehicle 06 (GPS III SV06) launched from Cape Canaveral Space Force S Satellites can be used to detect waste sites on Earth

A new computational system uses satellite data to identify sites on land where people dispose of waste, providing a new tool to monitor waste and revealing sites that may leak plastic into waterways. Caleb Kruse of Earthrise Media in Berkeley, California, Dr. Fabien Laurier from the Minderoo Foundation in Washington DC, and colleagues present this method in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on Ja

A new computational system uses satellite data to identify sites on land where people dispose of waste, providing a new tool to monitor waste and revealing sites that may leak plastic into waterways. Caleb Kruse of Earthrise Media in Berkeley, California, Dr. Fabien Laurier from the Minderoo Foundation in Washington DC, and colleagues present this method in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on Ja Can you trust your quantum simulator

At the scale of individual atoms, physics gets weird. Researchers are working to reveal, harness, and control these strange quantum effects using quantum analog simulators - laboratory experiments that involve super-cooling tens to hundreds of atoms and probing them with finely tuned lasers and magnets.

Scientists hope that any new understanding gained from quantum simulators will provide

At the scale of individual atoms, physics gets weird. Researchers are working to reveal, harness, and control these strange quantum effects using quantum analog simulators - laboratory experiments that involve super-cooling tens to hundreds of atoms and probing them with finely tuned lasers and magnets.

Scientists hope that any new understanding gained from quantum simulators will provide HawkEye 360 to monitor GPS interference in support of the US Space Force

HawkEye 360 Inc., the world's leading commercial provider of space-based radio frequency (RF) data and analytics, announced that Slingshot Aerospace awarded the RF data provider a contract to provide data for Slingshot's space-based monitoring and detection of RF threats and to support Slingshot's proliferated Low Earth Orbit (pLEO) Data Exploitation and Enhanced Processing (DEEP) program for th

HawkEye 360 Inc., the world's leading commercial provider of space-based radio frequency (RF) data and analytics, announced that Slingshot Aerospace awarded the RF data provider a contract to provide data for Slingshot's space-based monitoring and detection of RF threats and to support Slingshot's proliferated Low Earth Orbit (pLEO) Data Exploitation and Enhanced Processing (DEEP) program for th NASA issues award for greener, more fuel-efficient airliner of future

NASA announced Wednesday it has issued an award to The Boeing Company for the agency's Sustainable Flight Demonstrator project, which seeks to inform a potential new generation of green single-aisle airliners.

Under a Funded Space Act Agreement, Boeing will work with NASA to build, test, and fly a full-scale demonstrator aircraft and validate technologies aimed at lowering emissions.

NASA announced Wednesday it has issued an award to The Boeing Company for the agency's Sustainable Flight Demonstrator project, which seeks to inform a potential new generation of green single-aisle airliners.

Under a Funded Space Act Agreement, Boeing will work with NASA to build, test, and fly a full-scale demonstrator aircraft and validate technologies aimed at lowering emissions.