Copernical Team

Tomorrow’s technology centre

Image:

Tomorrow’s technology centre

Image:

Tomorrow’s technology centre Nigeria, Rwanda become first African countries to join NASA's Artemis Accord

Nigeria and Rwanda became the first and second African countries to sign NASA's Artemis Accord Tuesday.

They are the 22nd and 23rd countries to sign the accord overall. The cooperation between U.S. and African space agencies comes with a pledge to advance space exploration and address issues on Earth such as climate change and the global food crisis.

"The Artemis Accord is all ab

Nigeria and Rwanda became the first and second African countries to sign NASA's Artemis Accord Tuesday.

They are the 22nd and 23rd countries to sign the accord overall. The cooperation between U.S. and African space agencies comes with a pledge to advance space exploration and address issues on Earth such as climate change and the global food crisis.

"The Artemis Accord is all ab NASA starts RS-25 engine testing for future Artemis missions

NASA will start hot fire testing for the production of new RS-25 engines that will power future Artemis missions to the Moon, and eventually Mars.

The initial single-engine hot fire test Wednesday, at Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis in Mississippi, will run for 500 seconds starting at 2 p.m. CST.

"It is exciting to return to hot fire testing at the historic Fred Haise Tes

NASA will start hot fire testing for the production of new RS-25 engines that will power future Artemis missions to the Moon, and eventually Mars.

The initial single-engine hot fire test Wednesday, at Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis in Mississippi, will run for 500 seconds starting at 2 p.m. CST.

"It is exciting to return to hot fire testing at the historic Fred Haise Tes MTG-I1 launch coverage

Video:

03:13:00

Video:

03:13:00

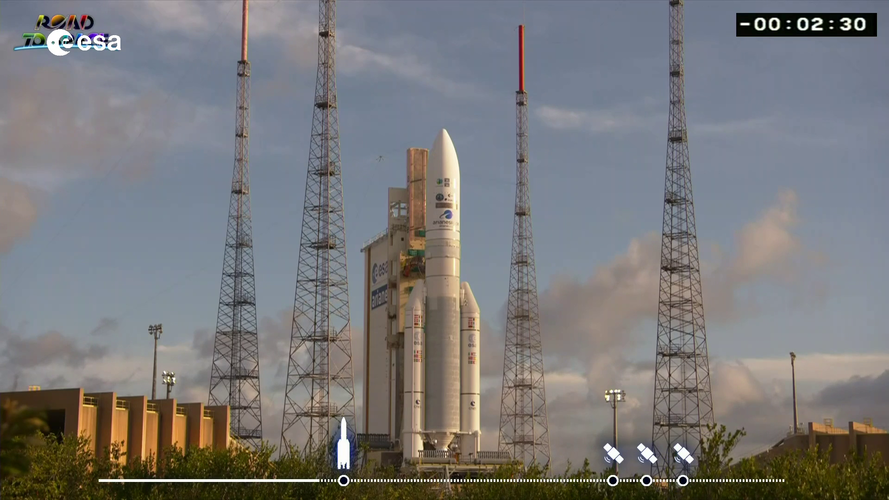

Watch the replay the MTG-I1 launch coverage. The video includes streaming of the event at ESA’s ESTEC establishment in the Netherlands and footage of liftoff from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana.

The first Meteosat Third Generation Imager (MTG-I1) satellite lifted off on an Ariane 5 rocket from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana on 13 December at 21:30 CET.

From geostationary orbit, 36,000 km above the equator, this all-new weather satellite will provide state-of-the art observations of Earth’s atmosphere and realtime monitoring of lightning events, taking weather forecasting to the next level. The satellite carries two completely new instruments: Europe’s

With success of Artemis I, when will NASA fly Artemis II?

With Orion safe back on Earth, the last and most important tests of the Artemis I mission have been completed, but there are still miles to travel and months of data sifting to go before NASA will target an Artemis II launch date.

While the latest announced timeline for that flight is no earlier than May 2024—only 18 months away—NASA officials after Sunday's successful landing kept referring a two-year turnaround between Artemis I and II, which would put its launch closer to the end of 2024.

"I think one thing we've always been concerned about is, what do we learn from [Artemis I] and are there changes we have to make? I think we've learned a lot," said Jim Free, NASA's associate administrator for the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate during a post-landing press conference Sunday.

"We obviously want to try to do it quicker," Free said, and pointed out the Orion team is "always looking to ways to do things quicker. We're trying to roll in lessons learned from the processing of the Artemis I vehicle at Kennedy. Are there things we can shorten there? Optimize? So that's all of our lessons learned path going forward.

NASA’s Big 2022: Historic Moon Mission, Webb Telescope Images, More

2022 is one for the history books as NASA caps off another astronomical year.

2022 is one for the history books as NASA caps off another astronomical year. Europe’s all-new weather satellite takes to the skies

Image:

Europe’s all-new weather satellite takes to the skies

Image:

Europe’s all-new weather satellite takes to the skies MTG-I1 lifts off

Video:

00:03:33

Video:

00:03:33

The first Meteosat Third Generation Imager (MTG-I1) satellite lifted off on an Ariane 5 rocket from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana on 13 December at 21:30 CET.

From geostationary orbit, 36,000 km above the equator, this all-new weather satellite will provide state-of-the art observations of Earth’s atmosphere and realtime monitoring of lightning events, taking weather forecasting to the next level. The satellite carries two completely new instruments: Europe’s first Lightning Imager and a Flexible Combined Imager.

MTG-I1 is the first of six satellites that form the full MTG system, which will provide critical data for weather forecasting over the

A new era of weather forecasting begins

The Meteosat Third Generation Imager satellite, set to revolutionise short-term weather forecasting in Europe, lifted off on an Ariane 5 rocket at 21:30 CET (17:30 local time in Kourou) on 13 December from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana. Its solar panels deployed just over 75 minutes later.

Sound of a dust devil on Mars recorded for first time

The sound of a dust devil on Mars was recorded for the first time as the eye of the whirlwind swept over the top of NASA's Perseverance rover, a new study said Tuesday.

"We hit the jackpot" when the rover's microphone picked up the noise made by the dust devil overhead, the study's lead author Naomi Murdoch told AFP.

The researchers hope the recording will help to better understand the

The sound of a dust devil on Mars was recorded for the first time as the eye of the whirlwind swept over the top of NASA's Perseverance rover, a new study said Tuesday.

"We hit the jackpot" when the rover's microphone picked up the noise made by the dust devil overhead, the study's lead author Naomi Murdoch told AFP.

The researchers hope the recording will help to better understand the