Copernical Team

Uniting Europe: DLR Spearheads Responsive Satellite Deployment Network

The rapidly expanding realm of information technology is ever-dependent on unobstructed access to space-based data and communication networks, bringing the need for technical mechanisms that can safeguard, repair, reinforce, or develop essential space infrastructures to the forefront.

Ensuring new satellites can be placed and activated in orbit within a matter of hours or days is of prime

The rapidly expanding realm of information technology is ever-dependent on unobstructed access to space-based data and communication networks, bringing the need for technical mechanisms that can safeguard, repair, reinforce, or develop essential space infrastructures to the forefront.

Ensuring new satellites can be placed and activated in orbit within a matter of hours or days is of prime Webb Telescope catches glimpse of possible first-ever 'dark stars'

Austin TX (SPX) Jul 14, 2023

Stars beam brightly out of the darkness of space thanks to fusion, atoms melding together and releasing energy. But what if there's another way to power a star?

A team of three astrophysicists - Katherine Freese at The University of Texas at Austin, in collaboration with Cosmin Ilie and Jillian Paulin '23 at Colgate University - analyzed images from the James

Austin TX (SPX) Jul 14, 2023

Stars beam brightly out of the darkness of space thanks to fusion, atoms melding together and releasing energy. But what if there's another way to power a star?

A team of three astrophysicists - Katherine Freese at The University of Texas at Austin, in collaboration with Cosmin Ilie and Jillian Paulin '23 at Colgate University - analyzed images from the James China's methane-fueled rocket achieves global first with successful orbital insertion

The first successful orbital mission of a methane-fueled rocket has been accomplished by China, a significant breakthrough in the utilization of low-cost and environmentally friendly liquid propellants for carrier rockets. The rocket, known as ZQ 2 or Rosefinch 2, launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center located in China's northwestern Gobi Desert on Wednesday morning.

The Beijing

The first successful orbital mission of a methane-fueled rocket has been accomplished by China, a significant breakthrough in the utilization of low-cost and environmentally friendly liquid propellants for carrier rockets. The rocket, known as ZQ 2 or Rosefinch 2, launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center located in China's northwestern Gobi Desert on Wednesday morning.

The Beijing Rocket Lab readies launch of seven satellites from New Zealand

California-based Rocket Lab plans to launch seven miniature satellites that will gather data on Earth's atmosphere to improve weather forecasting, replace a decommissioned technology spacecraft and send twin navigation satellites into space.

This mission, which Rocket Lab calls Baby Come Back, will involve a launch on an Electron rocket as early as Friday from New Zealand's Mahia Peninsula

California-based Rocket Lab plans to launch seven miniature satellites that will gather data on Earth's atmosphere to improve weather forecasting, replace a decommissioned technology spacecraft and send twin navigation satellites into space.

This mission, which Rocket Lab calls Baby Come Back, will involve a launch on an Electron rocket as early as Friday from New Zealand's Mahia Peninsula Japan rocket engine explodes during test: official

A Japanese rocket engine exploded during a test on Friday, an official said, in the latest blow to the country's space agency.

The Epsilon S - an improved version of the Epsilon rocket that failed to launch in October - blew up "roughly 50 seconds after ignition", science and technology ministry official Naoya Takegami told AFP.

The testing site in the northern prefecture of Akita was

A Japanese rocket engine exploded during a test on Friday, an official said, in the latest blow to the country's space agency.

The Epsilon S - an improved version of the Epsilon rocket that failed to launch in October - blew up "roughly 50 seconds after ignition", science and technology ministry official Naoya Takegami told AFP.

The testing site in the northern prefecture of Akita was Astronauts' new rides for Artemis missions arrive at Kennedy Space Center

While the next humans to fly to the moon will rely on the Orion spacecraft for the nearly half-million-mile trip next year on the Artemis II mission, the final 9 miles to the launch pad will come while riding in one of three new astronaut transports now parked at Kennedy Space Center.

Three curvy electric vehicles officially referred to as CTVs, as in crew transportation vehicles, were built by California-based Canoo Technologies and arrived to KSC on Tuesday. They will be used during training leading up to the Artemis II flight slated for no earlier than November 2024.

That mission will fly the crew of three NASA astronauts and one Canadian Space Agency astronaut on a 10-day mission around the moon, the first time humans will fly in the Orion capsule launching atop the powerful Space Launch System rocket. It will pave the way for Artemis III no earlier than 2025 that seeks to return humans including the first woman to the lunar surface for the first time since 1972.

The new zero-emission CTVs are equipped to bring the four crew suited up in their spacesuits along with support personnel including a spacesuit technician on the ride from the Neil A.

Virgin Galactic plans its next commercial flight to the edge of space for August

Preventing traffic accidents to the moon and back

Plasma spectrometer delivered for moon mission

Southwest Research Institute has delivered a plasma spectrometer for integration into a lunar lander as part of NASA's Lunar Vertex investigation, scheduled to commence next year.

Decoding the impact flash created by high-velocity impacts

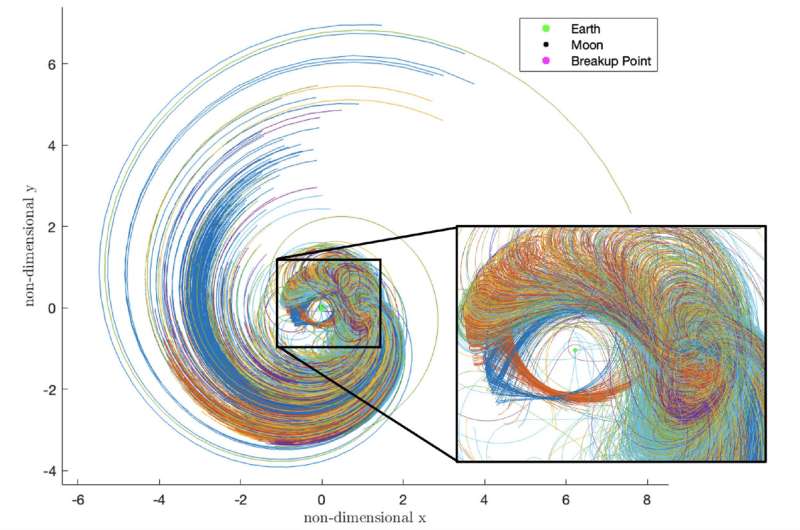

In an experimental study published in PNAS Nexus, researchers explore the visible impact flash that is created by high-velocity impacts.

Impacts by debris and meteoroids pose a significant threat to satellites, space probes, and hypersonic craft. Such high-velocity impacts create a brief, intense burst of light, known as an impact flash, which contains information about both the target and the impactor.

Gary Simpson, K.T. Ramesh, and colleagues explored the impact flash by shooting stainless steel spheres into an aluminum alloy plate, at a speed of three kilometers per second—about 6,700 miles per hour, or more than nine times the speed of sound.

The resulting impact flashes were photographed using ultra-high-speed cameras and high-speed spectroscopy, which measures the color and brightness of the light. Immediately after impact, a luminous disk is seen expanding around the impacting sphere. Only a few millionths of a second later, the disk takes on an almost floral shape, as fragments ejected from the impact crater form an ejecta cone, with petal-like projections at the outer edge.